My comrade Pete Veilleux, native plant landscaper and bushwhacking enthusiast nonpareil, asked if I would like to join him on a hike to see a secret corner of Oakland. Not far from his house in the teeming East Bay 'hood where oaks no longer grow, steep mountains cleave the landscape and bulwark an ancient, fragrant forest of bay, oak, and madrone. So we climbed the ridge between Cull Canyon and the Upper San Leandro watershed, near Dinosaur Peak so-called for its rocky outcrops like the spiky plates of a stegosaurus, to seek out some of our favorite native plants and the hidden connections lurking in the everyday.

My comrade Pete Veilleux, native plant landscaper and bushwhacking enthusiast nonpareil, asked if I would like to join him on a hike to see a secret corner of Oakland. Not far from his house in the teeming East Bay 'hood where oaks no longer grow, steep mountains cleave the landscape and bulwark an ancient, fragrant forest of bay, oak, and madrone. So we climbed the ridge between Cull Canyon and the Upper San Leandro watershed, near Dinosaur Peak so-called for its rocky outcrops like the spiky plates of a stegosaurus, to seek out some of our favorite native plants and the hidden connections lurking in the everyday.

No trail marked our route; we parked on a friend's private property and walked for a spell up an old fire road, then plunged into the underbrush. Directions? We headed due southwest and uphill.

Veilleux waxed rhapsodic about the bay trees all around us: the manifold shapes of trunk, the lush color of the leaves when they catch the sun, and above all the scent, that wonderful smell. "I think Umbellularia californica is the most versatile and under-used California native plant in the landscaping trade," he said.

"Not in my yard," I replied. The mature bay reaches heights of 120 feet, and as wide. He allowed that regular pruning for size might be necessary. Mixed among the bays all around us, oaks and madrones whispered in the wind as if in awe of the bay's position as climax forest community, the ultimate dispatcher of other trees in the ecosystem.

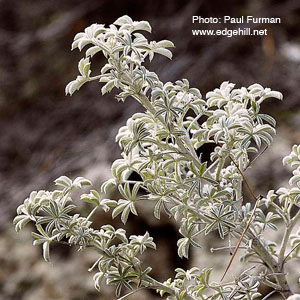

Few explorers would expect to find a beach hidden in the middle of a redwood grove. Yet such incongruities lurk in the mountains above Santa Cruz, where ancient seabeds upthrust millions of years ago by tectonic turmoil gave rise to stark hills of sand now tucked among lush evergreen forests more than five miles from the sea. Fossilized sand dollars and shark teeth in the ground testify to the marine origin of these Santa Cruz sandhills, whose so-called Zayante soils support a rare and unusual community of native plants found no place else on earth.

Few explorers would expect to find a beach hidden in the middle of a redwood grove. Yet such incongruities lurk in the mountains above Santa Cruz, where ancient seabeds upthrust millions of years ago by tectonic turmoil gave rise to stark hills of sand now tucked among lush evergreen forests more than five miles from the sea. Fossilized sand dollars and shark teeth in the ground testify to the marine origin of these Santa Cruz sandhills, whose so-called Zayante soils support a rare and unusual community of native plants found no place else on earth.

On two sides of the Old Sonoma Highway, one such meadow is divided by two authorities. The southwest side of the field falls within the boundaries of

On two sides of the Old Sonoma Highway, one such meadow is divided by two authorities. The southwest side of the field falls within the boundaries of  Passover comes this Sunday, a rite from the Biblical story of Exodus, wherein the enslaved Israelites win their freedom from Pharaoh. It seems a fitting context for a discussion of The Acres, an indentured ecosystem on the wildland-urban interface.

Passover comes this Sunday, a rite from the Biblical story of Exodus, wherein the enslaved Israelites win their freedom from Pharaoh. It seems a fitting context for a discussion of The Acres, an indentured ecosystem on the wildland-urban interface. Often charming, occasionally gritty, surely up-and-coming -- witness the real estate renaissance of Bernal Heights, S.F.'s neo-boho neighborhood where once-dilapidated homes now zoom at the speed of commerce beyond the million dollar threshold. Yet a liferaft floating at the center of this frothing urban sea remains undeveloped: Bernal Hill Park, a peak with a far older balance sheet of life, death, and rebirth.

Often charming, occasionally gritty, surely up-and-coming -- witness the real estate renaissance of Bernal Heights, S.F.'s neo-boho neighborhood where once-dilapidated homes now zoom at the speed of commerce beyond the million dollar threshold. Yet a liferaft floating at the center of this frothing urban sea remains undeveloped: Bernal Hill Park, a peak with a far older balance sheet of life, death, and rebirth. The trappings of prosperity pursued by contemporary city dwellers emphasize the appeal of "living large," hinting that the ends of financial aggrandizement will justify any means. But here in the Bay Area, we also enjoy a wealth of nearby natural resources that remind us of just how small any one person is in the grander scheme of Earth. These two sides of the spectrum meet in the old-growth redwood forest of Muir Woods, located only 15 miles north of San Francisco's financial district yet rooted in a time that predates our mercantile madness by millions of years.

The trappings of prosperity pursued by contemporary city dwellers emphasize the appeal of "living large," hinting that the ends of financial aggrandizement will justify any means. But here in the Bay Area, we also enjoy a wealth of nearby natural resources that remind us of just how small any one person is in the grander scheme of Earth. These two sides of the spectrum meet in the old-growth redwood forest of Muir Woods, located only 15 miles north of San Francisco's financial district yet rooted in a time that predates our mercantile madness by millions of years. "I just hiked to the top of Cedar Mountain Ridge," wrote Pete Veilleux, proprietor of East Bay Wilds landscaping, "and found some very cool plants including a bigberry manzanita 40 feet tall!"

"I just hiked to the top of Cedar Mountain Ridge," wrote Pete Veilleux, proprietor of East Bay Wilds landscaping, "and found some very cool plants including a bigberry manzanita 40 feet tall!" The well-groomed greenery of San Francisco's Golden Gate Park demonstrates the power of mankind to transform an uncultivated landscape into a recreational playground. Once a windswept wildland, these former sand dunes and occasional oak groves were staked out in the late 19th century by massive plantings of eucalyptus and monterey pine, thereby stabilizing the sandbank and forming the foundation into which horticulture could sink its roots. Great lawns and buffalo paddocks, rose gardens and tulip beds, an arboretum and a Japanese tea garden and a conservatory of flowers and more arose to meet the desires of a growing city and its park-loving public.

The well-groomed greenery of San Francisco's Golden Gate Park demonstrates the power of mankind to transform an uncultivated landscape into a recreational playground. Once a windswept wildland, these former sand dunes and occasional oak groves were staked out in the late 19th century by massive plantings of eucalyptus and monterey pine, thereby stabilizing the sandbank and forming the foundation into which horticulture could sink its roots. Great lawns and buffalo paddocks, rose gardens and tulip beds, an arboretum and a Japanese tea garden and a conservatory of flowers and more arose to meet the desires of a growing city and its park-loving public. November rain sings a song of connectivity. It completes the natural cycle, raising the rivers and recharging the aquifers, pouring from the air to the earth and back to the ocean whence it came. We find an extraordinary example of its ramifications in western Marin County, where the rainfall not only paints a fresh coat of green on the sun-blasted hills but also summons a legion of deep sea creatures to return to the highland haunts of their birth.

November rain sings a song of connectivity. It completes the natural cycle, raising the rivers and recharging the aquifers, pouring from the air to the earth and back to the ocean whence it came. We find an extraordinary example of its ramifications in western Marin County, where the rainfall not only paints a fresh coat of green on the sun-blasted hills but also summons a legion of deep sea creatures to return to the highland haunts of their birth. At the confluence of Redwood Creek and San Francisco Bay in southern San Mateo county, three islands shape-shift in drifting piles of river silt and sea salt. Boundaries may blur, but Smith and Corkscrew Sloughs divide this trio clearly into Inner, Middle, and Outer Bair Island -- the first a popular Redwood City jogging and dog-walking spot connected to the mainland at Whipple Ave., the latter two accessible by kayak. These sandbanks and mudflats have undulated over eons in a long, slow waltz between sedimentation from the river and erosion from the tides, creation and destruction inseparable.

At the confluence of Redwood Creek and San Francisco Bay in southern San Mateo county, three islands shape-shift in drifting piles of river silt and sea salt. Boundaries may blur, but Smith and Corkscrew Sloughs divide this trio clearly into Inner, Middle, and Outer Bair Island -- the first a popular Redwood City jogging and dog-walking spot connected to the mainland at Whipple Ave., the latter two accessible by kayak. These sandbanks and mudflats have undulated over eons in a long, slow waltz between sedimentation from the river and erosion from the tides, creation and destruction inseparable. On a

mountain range in Oakland, a lioness prowls her historic canyon.

Rugged ridges and riotous riparian zones cleave the oak woodlands

and chaparral into complementary halves. This is the intersection

of sunlight and shadow,

of wilderness and the urban, of knowledge and the unknown.

On a

mountain range in Oakland, a lioness prowls her historic canyon.

Rugged ridges and riotous riparian zones cleave the oak woodlands

and chaparral into complementary halves. This is the intersection

of sunlight and shadow,

of wilderness and the urban, of knowledge and the unknown.

Water and sand straddle the symbolic spectrum of living: while the former is biologically essential, the latter evokes the lifeless dunes of the desert. Yet here in San Francisco, where dunes define our geology and "normal" is anything but, the sandy banks of our largest lake sustain a population of drought-tolerant dune plants that belie the dominant paradigm. Such a flourishing of life under inauspicious circumstances distinguishes our local flora.

Water and sand straddle the symbolic spectrum of living: while the former is biologically essential, the latter evokes the lifeless dunes of the desert. Yet here in San Francisco, where dunes define our geology and "normal" is anything but, the sandy banks of our largest lake sustain a population of drought-tolerant dune plants that belie the dominant paradigm. Such a flourishing of life under inauspicious circumstances distinguishes our local flora. Words bestow immortality: just as the book outlives its author, a name can outlast its human corollary. Many California landmarks bear the names of historic families, for example, providing a subtext that enhances our sense of local identity. The story behind each name can add even greater value, much like the bones of our ancestors that enrich the earth in deepening layers of fertility.

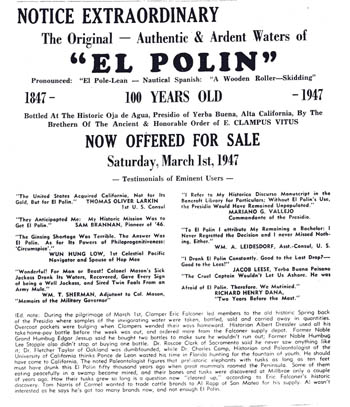

Words bestow immortality: just as the book outlives its author, a name can outlast its human corollary. Many California landmarks bear the names of historic families, for example, providing a subtext that enhances our sense of local identity. The story behind each name can add even greater value, much like the bones of our ancestors that enrich the earth in deepening layers of fertility. Predicting the future or understanding the past -- which is more important? Ask the Muwekma Ohlone, who settled the village of Petlenuc beside El Polin some 5,000 years ago; they knew lots about the local plants and animals, but had no idea this land would become the Presidio of San Francisco, one of the most valuable pieces of real estate in the world. Their simple life ended with the 1776 arrival of Captain Anza, who chained them up and founded this fort as the northernmost reach of the Spanish crown. The following two centuries of military occupation under the flags of Spain, Mexico, and the U.S. shocked and awed this landscape into spectacular transformation, but neither quadrangles nor barracks nor landfills nor quarries nor the gloom of an historic Australian forest have stayed the original native plant communities from their appointed lifecycles: many of the "original inhabitants" still grow on the Presidio's distinctive bluffs, beaches, and dunes, telling a tale older than mankind.

Predicting the future or understanding the past -- which is more important? Ask the Muwekma Ohlone, who settled the village of Petlenuc beside El Polin some 5,000 years ago; they knew lots about the local plants and animals, but had no idea this land would become the Presidio of San Francisco, one of the most valuable pieces of real estate in the world. Their simple life ended with the 1776 arrival of Captain Anza, who chained them up and founded this fort as the northernmost reach of the Spanish crown. The following two centuries of military occupation under the flags of Spain, Mexico, and the U.S. shocked and awed this landscape into spectacular transformation, but neither quadrangles nor barracks nor landfills nor quarries nor the gloom of an historic Australian forest have stayed the original native plant communities from their appointed lifecycles: many of the "original inhabitants" still grow on the Presidio's distinctive bluffs, beaches, and dunes, telling a tale older than mankind. Daily we drive our cars or ride the bus to the city, glad for modern transportation yet melancholy for the fate of paved-over Nature, a presumed paradise lost. But pockets of the original wilderness still flourish among our Bay Area motorways, just as a rare flower might sprout unnoticed in the middle of a sun-baked field. These natural sanctuaries are portals that can transport us to an earlier time. In Marin County, for example, where the Tiburon peninsula meets the mainland, surrounded by Corte Madera's housing developments and adjacent to Hwy. 101, the open space preserve at Ring Mountain sustains a living connection with history, a lifeline to yesterday's forgotten truths.

Daily we drive our cars or ride the bus to the city, glad for modern transportation yet melancholy for the fate of paved-over Nature, a presumed paradise lost. But pockets of the original wilderness still flourish among our Bay Area motorways, just as a rare flower might sprout unnoticed in the middle of a sun-baked field. These natural sanctuaries are portals that can transport us to an earlier time. In Marin County, for example, where the Tiburon peninsula meets the mainland, surrounded by Corte Madera's housing developments and adjacent to Hwy. 101, the open space preserve at Ring Mountain sustains a living connection with history, a lifeline to yesterday's forgotten truths. Shifting identities and strange alliances occur along the wildland-urban interface, where natural ecosystems collide with cities and the side effects of human industry. Plants and animals living along these intersections must adapt to changing conditions, or perish. We now raise the curtain on a drama where cows protect rare and endangered butterflies from certain death by automobile, with a dramatis personae of native wildflowers and exotic grasses playing supporting roles.

Shifting identities and strange alliances occur along the wildland-urban interface, where natural ecosystems collide with cities and the side effects of human industry. Plants and animals living along these intersections must adapt to changing conditions, or perish. We now raise the curtain on a drama where cows protect rare and endangered butterflies from certain death by automobile, with a dramatis personae of native wildflowers and exotic grasses playing supporting roles. Once upon a time, Twin Peaks stood as one mountain, a united man and wife. But the couple quarreled long and bitterly, until at last the Great Spirit cleaved them with a bolt of lightning. The neighborhood has been quiet ever since -- or so say the chroniclers of Indian legend.

Once upon a time, Twin Peaks stood as one mountain, a united man and wife. But the couple quarreled long and bitterly, until at last the Great Spirit cleaved them with a bolt of lightning. The neighborhood has been quiet ever since -- or so say the chroniclers of Indian legend. Here in earthquake country, the land moves in puzzling ways. Take Montara Mountain, a San Mateo landmark at the uppermost edge of the Santa Cruz Range, whose steep heights plunge dramatically through the fog down into the sea at Devil's Slide. It looks like the western edge of North America, but in fact this granite and sandstone formation sits on the eastern edge of the Pacific plate, a tectonic "island" riding north along the shear of the San Andreas Fault. This mountain originated with the sierra of Southern California, and has been grinding its long, bumpy way up the coast toward San Francisco for millions of years, at speeds approaching one meter per century.

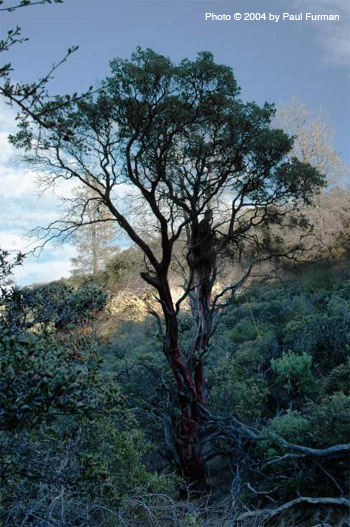

Here in earthquake country, the land moves in puzzling ways. Take Montara Mountain, a San Mateo landmark at the uppermost edge of the Santa Cruz Range, whose steep heights plunge dramatically through the fog down into the sea at Devil's Slide. It looks like the western edge of North America, but in fact this granite and sandstone formation sits on the eastern edge of the Pacific plate, a tectonic "island" riding north along the shear of the San Andreas Fault. This mountain originated with the sierra of Southern California, and has been grinding its long, bumpy way up the coast toward San Francisco for millions of years, at speeds approaching one meter per century. Leave your car in the parking lot on Skyline Blvd. in the Oakland Hills and step through the unknown, remembered gate onto the huckleberry path. Inhale the aroma of rain on the wind, a perfume mixed with the bouquet of a mature bay forest. Sheer rocky knolls punctuate the canyon, its story a potboiler of earthquakes and eruptions. Mist drapes maverick oaks and madrones in fleeting gossamer gowns, and paints the tops of trees on the ridge across the valley. The voice of the river rises from below, a music older than memory.

Leave your car in the parking lot on Skyline Blvd. in the Oakland Hills and step through the unknown, remembered gate onto the huckleberry path. Inhale the aroma of rain on the wind, a perfume mixed with the bouquet of a mature bay forest. Sheer rocky knolls punctuate the canyon, its story a potboiler of earthquakes and eruptions. Mist drapes maverick oaks and madrones in fleeting gossamer gowns, and paints the tops of trees on the ridge across the valley. The voice of the river rises from below, a music older than memory.