Predicting the future or understanding the past -- which is more important? Ask the Muwekma Ohlone, who settled the village of Petlenuc beside El Polin some 5,000 years ago; they knew lots about the local plants and animals, but had no idea this land would become the Presidio of San Francisco, one of the most valuable pieces of real estate in the world. Their simple life ended with the 1776 arrival of Captain Anza, who chained them up and founded this fort as the northernmost reach of the Spanish crown. The following two centuries of military occupation under the flags of Spain, Mexico, and the U.S. shocked and awed this landscape into spectacular transformation, but neither quadrangles nor barracks nor landfills nor quarries nor the gloom of an historic Australian forest have stayed the original native plant communities from their appointed lifecycles: many of the "original inhabitants" still grow on the Presidio's distinctive bluffs, beaches, and dunes, telling a tale older than mankind.

Predicting the future or understanding the past -- which is more important? Ask the Muwekma Ohlone, who settled the village of Petlenuc beside El Polin some 5,000 years ago; they knew lots about the local plants and animals, but had no idea this land would become the Presidio of San Francisco, one of the most valuable pieces of real estate in the world. Their simple life ended with the 1776 arrival of Captain Anza, who chained them up and founded this fort as the northernmost reach of the Spanish crown. The following two centuries of military occupation under the flags of Spain, Mexico, and the U.S. shocked and awed this landscape into spectacular transformation, but neither quadrangles nor barracks nor landfills nor quarries nor the gloom of an historic Australian forest have stayed the original native plant communities from their appointed lifecycles: many of the "original inhabitants" still grow on the Presidio's distinctive bluffs, beaches, and dunes, telling a tale older than mankind.

Among our oldest local legends concerns the Oja de Agua of El Polin, a freshwater spring in the Tennessee Hollow watershed (the Presidio's southeast corner). The bulk of the military's water supply always came from Mountain Lake to the west, but the seasonal pulse of El Polin commanded greater mystery and attraction. Myth held that any maiden who drank of its waters (particularly during a full moon) would be assured great fertility with an abundance of twins, while any man so indulging would enjoy a vigorous jolt of pre-Columbian Viagra. In his Discorso Historica of 1876, General Vallejo described the "very good water" which "demonstrated miraculous qualities"; he cited the numerous offspring of garrison wives, "all of whom several times had twins," and listed them by family name and number of children produced (13, 18, 22), a laudable multiplication he attributed to "the virtue of the water of El Polin, which still exists."

The name El Polin derives from the old Spanish word for a giant wooden roller used dockside to load cannon and treasure aboard galleons; due to the phallic appearance of these logs, the word enjoyed widespread use as vulgar slang for the penis. Sources hint at Ohlone origins for the legend of the water's fucundity, but the nickname is 100% macho Spaniard.

El Polin's intrigue grew over the years, with conflicting reports of the "true source" and various factions taking oaths to keep the site secret from one another. But debating the exact whereabouts of the magic spring is moot; this wellspring is one of several (including a fountain in the courtyard of St. Mary the Virgin Church at Union and Steiner) fed by groundwater draining through the sandstone and serpentine ridge that peaks at Clay Street. Flow patterns have shifted over eons with the sand dunes -- and more recently, with the bulldozers.

The modern map of the Presidio marks "El Polin Spring" at the southern foot of MacArthur Ave., in a cozy picnic area outfitted with a cobblestone well to mark the location. The water draining from the hillside to the well tumbles over some beautiful Spanish-era brickworks in a series of miniature waterfalls, attracting birds who like to drink and shower in the cascades. Copious in February when charged by rainfall, the flow here in June has slowed to five or ten cups per minute, and will dry to less than a trickle in October.

Still, the native plant community of El Polin is characteristic of some riparian habitats, testifiying to the water seeping underground. Wax myrtle or Myrica californica grows evergreen to fifteen feet, a desireable shelter for wildlife. The 3-foot perennial bee plant or Scrophularia californica feeds a squadron of swooping hummingbirds, while scattered rushes (Juncus leseurii, J. phaeocephalus, and J. effusus) and willows (Salix spp.) further confirm the presence of groundwater.

Still, the native plant community of El Polin is characteristic of some riparian habitats, testifiying to the water seeping underground. Wax myrtle or Myrica californica grows evergreen to fifteen feet, a desireable shelter for wildlife. The 3-foot perennial bee plant or Scrophularia californica feeds a squadron of swooping hummingbirds, while scattered rushes (Juncus leseurii, J. phaeocephalus, and J. effusus) and willows (Salix spp.) further confirm the presence of groundwater.

Some members of the Presidio Trust have deduced from these water-loving plants that El Polin was once the headwaters for an open stream that flowed north to the Bay, and they plan to "daylight the stream" by digging up pipes and building three "natural waterways" from Tennessee Hollow that will drain into a central creek running to the newly restored wetlands at Crissy Field. Opponents of this plan, like environmental justice advocate Francisco Da Costa and native plant booster Susan M. Smith, state that no such stream ever existed; they denounce the project as a bid by the Trust to salvage their "failed wetlands" with an increased flow of fresh water through what was once sand dunes, not open creek. (The Crissy tidal marsh has inded grown silted with deposits of sand, and toxic levels of sewage were found in its shallows.)

We have descriptions of the Presidio at the turn of the 19th century by pioneering naturalists Menzies and Chamisso, an early view of this landscape before it was so helplessly wrangled by western civilization. From the journal of Archibald Menzies, describing his expedition with Capt. Vancouver to the terrain of present-day Crissy lagoon, written in 1792 (copy on file in the library of the California Academy of Sciences): "We found a low tract of marshy land with some saltwater lagoons supplied by the overflowing of high tides and oozing through the sandy beach... The watering party who landed before us could meet with no fresh water stream. They were therefore obliged to dig a well in the marsh to fill their casks, which was a little brackish, as might be expected."

From the journal of Adelbert von Chamisso on his first visit to the Presidio in 1816 (copy on file in the library of the Presidio Trust): "We had taken on fresh water, which in this port, especially in summer, is a difficult business." His ship, the Russion schooner Rurick, was anchored in view of the main post, at the mouth of any existing wetland from that time.

An 1839 map of San Francisco drawn by Smith Elder of London clearly shows east-running Islais, Mission, and Yosemite Creeks by the Mission, and a 1776 map by Pedro Font of the original Anza expedition shows Mountain Lake with Lobos Creek running west to the sea, but neither map shows a north-running waterway beside the fortress -- only some wavy lines drawn to the north in the swampy region by the shore.

Today, on the slope rising above El Polin to Inspiration Point, a serpentine grassland boasts a population of the federally endangered Presidio Clarkia or Clarkia franciscana. This slender annual with the light-green foliage brightens the hillside every June with delicate pink-purple blossoms held 12-18 inches high. This is one of our most rare and prized endemics, growing here in rich association with blue trumpets of Ithuriel's spear (Triteleia laxa), fragrant white twilight blossoms of soap plant (Chlorogalum pomeridianum), and hot pink flashes of wild onion (Allium dichlamydeum). All these plants depend on water draining slowly through the fractures of the underlying serpentine, but much of this water may be squandered by the installation of an open stream below the springs. Might the protected Clarkia be affected? Says Smith, "Putting in drains below El Polin (so-called "daylighting") would put this population in jeopardy."

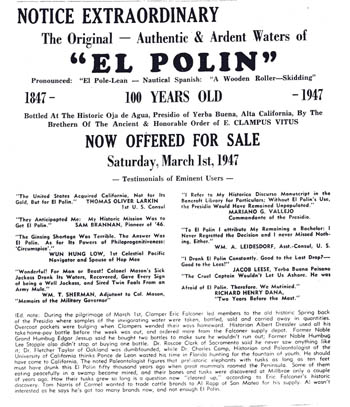

Snake oil comes in many flavors, and El Polin has spawned its share of shills. A flyer titled "Notice Extraordinary" from 1947 announced a one-day sale of "the original, authentic and ardent waters of El Polin, bottled by the Brethren of the Ancient & Honorable Order of E. Clampus Vitus." A librarian's footnote identifies the responsible scoundrel as Army clamper Eric Falconer, who embellished his advertisement with fabricated testimonials of eminent users such as "Wonderful! For man or beast! Colonel Mason's sick jackass drank its waters, recovered, gave every sign of being a well jackass, and sired twin foals from an Army mule." Whether his intended customers were jackasses or stevedore's poles, Falconer's fandango may bear an eerie parallel to contemporary schemes. Seduced by the romance of El Polin, those who would narrate its future must not forget its past. The stories are out there for anyone willing to hear. Pause with me for a moment, and listen.

* * *

Writer and landscape designer Geoffrey Coffey is reminded of the poem "Ozymandias" by Percy Shelley. Find Coffey's vast and trunkless legs of stone at www.geoffreycoffey.com.